“Automatisms are stupid”. This was a headline I recently read on Twitter, followed up by an article that I couldn’t wait to read. As a proponent of automatisms, I felt a jolt of energy to hear all about why they were stupid. The argument, essentially, was what we’ve all heard about isolated technical training over the years – that they cannot directly be applied to the actual game. The word “automatisms” was used interchangeably with “passing patterns” – a typically isolated training technique where players are given instructions on the exact places on the pitch to pass a ball from one teammate to the next, unopposed. So first, let’s clarify something. While passing patterns can become automatisms, they are not the same thing, and cannot be used interchangeably.

EFFECTIVELY TRAINING AUTOMATISMS

Automatisms, at their core, directly apply to the game. That is the whole point to them. Managers like Ralph Hasenhuttl and (…everyone) train automatisms in relation to the four elements of the game – the opposition, the space, teammates, and the ball. What’s more, is that automatisms are generally trained in relation to off-the-ball events – focusing on movement patterns that can unlock the opposition, rather than specific on-the-ball sequences. Here’s a very common attacking automatism that we’ve all come to know and love.

The defensive midfielder receives the ball with time and space to get their head up, allowing the Liverpool false nine to seek space away from the opposition’s defense and drift into open space. As a consequence, the wide men can now drift into the newly vacated space in behind the opposition’s defense. Liverpool do this not as a sporadic in-the-moment feeling on what might be most appropriate. They do this as a direct result of patterns they’ve worked relentlessly on developing in training, within their game model. This then becomes an automatism.

What is an automatism? An automatism is a pattern of play specifically practiced in training to be used in either one specific game, or over the course of several matches, that is guided by the coach or manager’s ideals about the game. Based on the four elements of the game, players can then recognize moments in a match where they understand a correct action that they can take, allowing for an almost “automatic” process. Players are still free to make decisions based on what they see, as no situation is ever the same in football. However, by relentlessly practicing these situations in training, the decision making process can become enhanced. Why? Because by turning these decision making processes into muscle memory, players are more easily able to identify measures they can take in a quicker amount of time.

A false nine knows that when their defensive midfielder receives the ball in space and they too have space to move into, that they can drift toward the ball, opening room in behind for others to advance. If the moment fails to present itself in exactly the right way, the false nine can still make the decision to push the opposition’s defensive line back, rather than drifting in deep. Here we see why the decision making process has not been taken away by training automatisms, only heightened.

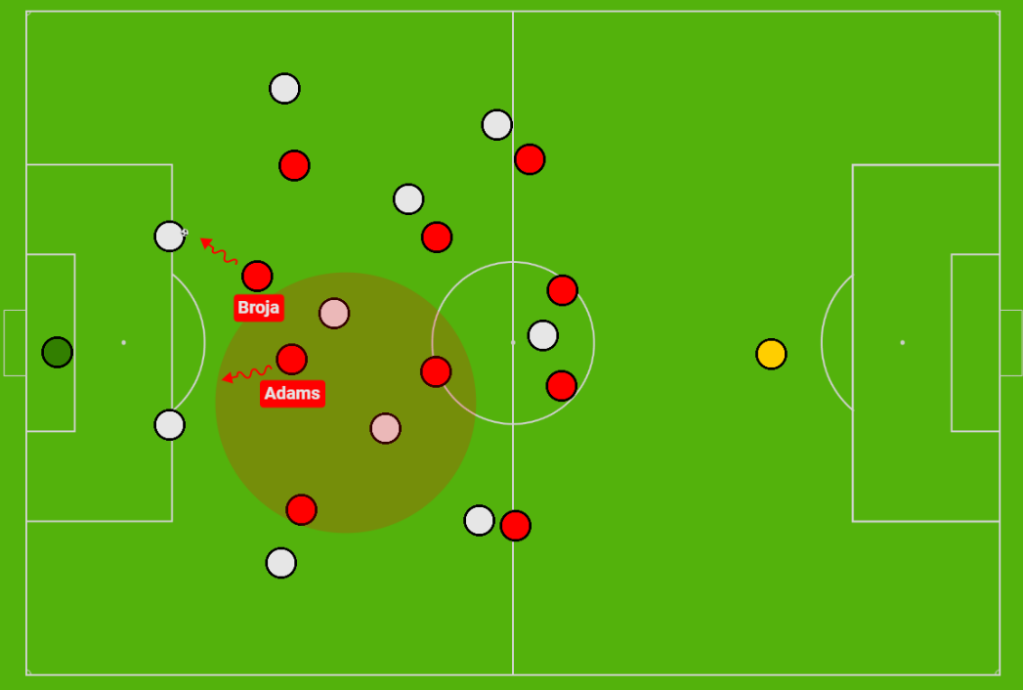

Here’s another common automatism – from the man most fervidly pushing the lingo. Ralph Hasenhuttl trains automatisms within his pressing structures – again an off-the-ball facet of the game. In his 4-2-2-2 pressing shape, Hasenhuttl works with his players to help them understand actions they can take based on the four elements of the game, helping his pressing ideologies become more automatic for his players. In the above example, we see that Broja cover shadows the opposition’s defensive midfielder as he presses the player in possession. The Southampton right winger also nicely covers two players at once, ready to anticipate either pass as the opposition centre-back shapes up to play in that direction. Adams can then read the situation, recognizing that the next logical pass would instead be to the player’s centre-back partner, and can anticipate that next action. If the opposition player makes a failed pass into midfield instead, Adams is now in a great position to help his team immediately counter attack toward goal. If the opposition player makes the pass toward his centre-back partner, Adams is ready to pounce. By guiding training toward helping players understand these concepts of space, opposition, teammates and the ball, Hasenhuttl has developed one of the most intensive and resilient pressing structures in the division, without ever limiting their decision making.

Here’s another common one that has allowed West Ham to achieve tremendous success this season. As Michail Antonio drifts wide to receive a long pass, Jarrod Bowen can immediately spring forward into the vacated central area of the pitch. The medical definition of an automatism states that an action becomes “unconscious”, without control. In the footballing sense, the action becomes more or less “unconscious”, with control. In other words, a player needs less time to think about where and when they should adopt a position or what action to take, based on what they see (not what the coach sees) within the four elements of the game.

IS THERE A PLACE FOR TECHNICAL TRAINING?

But what about passing patterns and “isolated” training? Well, they too can have a place in football. I’m not a proponent of players standing behind cones, waiting in lines, or performing the exact actions a coach wants them to. Coaches must always work to enhance decision making processes in their players, not reduce them. But I do see a value in training specific patterns of play in two different instances. The first is in finding ways to unlock the opposition. Wolves for example used highly distinguishable passing patterns in their 1-0 win over Manchester United this season. They utilized bounce passes in the right-half-space ahead of Harry Maguire, enticing him to do what he already loves to do, and leave his line to track an inverted winger or Jimenez. But instead of the Wolves player turning and taking Harry Maguire on 1v1, they quickly bounced the ball back to a nearby central midfielder, who could then spread play in the vacated space in behind.

This clearly coordinated sequence helped Wolves gain traction in the match. Rather than needing to simply sit deep and play on the break, they could gain their own foothold, and pass the ball around for fun in meaningful ways. They identified a weakness in Manchester United, and worked to find a “passing pattern” that could exploit it. It’s true that a match may evolve in completely unique and novel ways than expected, and that you cannot ever know exactly how an opposition team will play. But you can study patterns existing over time in the opposition, and work to identify ways for exploitation. This isn’t to say that players should be stuck behind cones working on these patterns in isolation and unopposed training “drills”, but that there is value in working on passing patterns within the realms of meticulously designed training activities, and small-sided-games.

In fact, this is how I utilized automatisms to coach an unbeaten team last summer. I almost-exclusively utilized small-sided-games to help my players understand correct actions they could take in all phases of the game. This allowed my players to have a clear understanding of their role in the team, buy-into the process of our over-arching identity as a team, and quickly make correct decisions based on the moment. I never told my players that in any given situation, they had to make a certain action. But we always related everything to teammates, opposition, ball and space, breaking down correct options; and allowing the players to collaboratively discover their own ideas around the best options available when stopping play in training. Those who question passing patterns and even automatisms are right to question isolated training techniques and their direct applicability to the game. But we cannot forget that anything, even technical components, can be trained within small-sided games.

When working on passing patterns, such as a diamond build-up shape between goalkeeper, defensive midfielder and two centre-backs, you can train that in the context of a small-sided game where the ball always restarts with these players in their exact positions, working on both the technical and tactical elements of playing out from the back. Passing patterns are not stupid, they’re just not always used in ways that can truly help the development of players.

That said, there is also a place for technical training to be used in isolation. From my perspective, that comes most prominently when working with players 1on1. In 1on1 situations, you can work closely with players to breakdown the anatomical, physical, technical and biological components to their various techniques and skills, and better allow for players to repeatedly perform actions until it becomes muscle memory (automatic). For example, I worked with a player 1on1 to have her repeatedly shoot the ball with her weaker left-foot, in game-realistic (albeit mostly unopposed) training activities. How do you make unopposed training game-realistic? That’s up to you as a coach to put pressure on the player to perform actions quickly, with a high degree of pace and precision.

The point of having it be unopposed is that the player can repeatedly work on their technique, without a defender constantly stealing the ball before they get a chance. From not being able to have the ball travel more than 10-metres, she now scores goals repeatedly with her left-foot. Why? Not only have the technical and physical skills improved in her power, accuracy, and understanding of timing; but it’s become automatic to her. She knows when the ball is travelling across her left foot, exactly how to angle her hips and body to allow for an easier way of striking the ball. She knows how to continue to angle her hips and follow-through in a way that ensures she finds the target. That’s because we broke down those anatomical components in isolation and had her repeatedly perform the action of timing a run and timing a left-footed finish, until it became second-nature. Did I ever have her just stand still and shoot the ball on her left-foot? No. There was always a recognition for space, time and the ball, even if not always opposition and teammates.

Stationary passing patterns are relatively ineffectual because they don’t account for the complexities listed above. Other than maybe direct free kicks, I don’t believe in training anything that requires players to be static. But again, not everything can fit into this box. For instance, why would all professional players juggle the ball for hours if technical training in isolation wasn’t useful? By juggling the ball, players actively work on their first touch, and the technical components to ball control, that then allow for direct applications to the game where they automatically control the ball on the drop of a dime.

Not to beat a dead horse (what a terrible expression that is), but off-the-ball movement is, of course, the most important facet to the game. But saying that all passing patterns or attempts to make decision making automatic are “stupid” fails to account for the fact that these things don’t have to be trained in isolation. After all, if they were stupid, why would coaches like Jurgen Klopp or Ralph Hasenhuttl deploy them as training methods?

Disagree? Let’s have a discussion. It’s all about helping each other learn about the game, and develop our craft. You can find me on social media @desmondrhys and @mastermindsite, or via any of the links below. Thanks for reading and see you soon!

You may also enjoy…

-> Why patterns and context are so essential to analysis in football

-> Coaching Automatisms – Rehearsed Patterns of Play

-> The simple task anyone can do to improve their tactical knowledge

DON’T FORGET TO CHECK OUT…

Chaos vs. Control: A Collision of Principles

Some like to approach games in a disciplined structure, intentionally and meticulously dictating games to their own tempo. Others opt for a more emotionally-charged philosophy, reliant on the belief, energy and willpower of their trusted eleven on the field.

Game of Numbers #37 – Forge FC’s use of centre-backs in midfield like Manchester City

For the unfamiliar, Forge FC are the Manchester City of the Canadian Premier League. They play a possession-based 4-3-3, stacked with ball-savvy savants, and a culture that embodies winning. The Canadian Premier League’s been around since 2019 now. Forge have won the Playoffs in four of the five seasons, and lost the final in the…

Why centre-backs are becoming fullbacks: The tactical trend that defined 2023

It might be wrong to credit this tactical approach to Pep Guardiola. After all, the origin story to the ‘fullback’ is because the defender was fully back. However, in operating with a centre-back that steps up into midfield, Guardiola also created a construction within his team that regularly positioned centre-backs out wide. From then on,…

Comparing the Canadian Premier League’s next best centre-forwards

The best strikers in the modern era are able to combine a vast array of skillsets. We’ve seen this play out in the CPL this season, with those unable to fully combine all the necessary skillsets also failing to turn their talents into goals. Here is my analysis of four of the next best centre-forwards…

11 thoughts on “I will change your mind about automatisms”