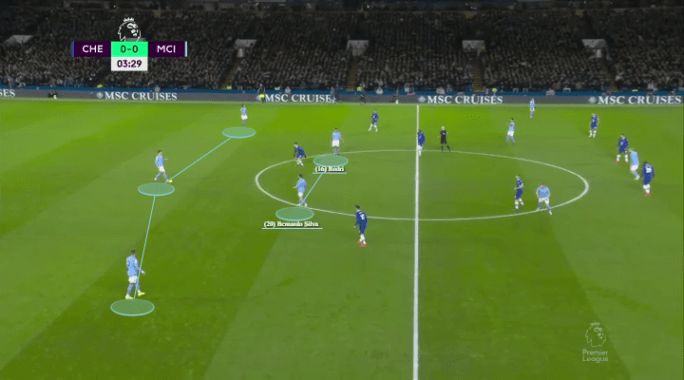

On January 5th, 2023, in a 1-0 win over Chelsea, Pep Guardiola whipped out a peculiar tactic that seemed destined to be a one-time tactical invention. Joao Cancelo and Kyle Walker, who had made a name for themselves as inverted fullbacks capable of stepping into midfield, were both in the team that day. So when the team sheets rolled out, a typical City styled 4-3-3 would have been more than expected. But for whatever reason, Guardiola opted for a different approach.

Manchester City built out from the back that day in a back-three formation, with Rodri and Bernardo Silva double-pivoting the midfield. Although it went against their typical 2+3 ‘Inverted Fullback’ build and seemed to position Phil Foden in an awkward wing-back role, the plan still positioned players in relative roles that made sense.

Embed from Getty ImagesBut then upon further examination, it became clear. Rodri wasn’t playing in midfield. He was a centre-back. A centre-back, that would step into midfield areas in possession, and then drop into the back-line out of possession. It seemed strange, but Rodri performed the role magnificently, always picking up the right space to help his team see out the victory.

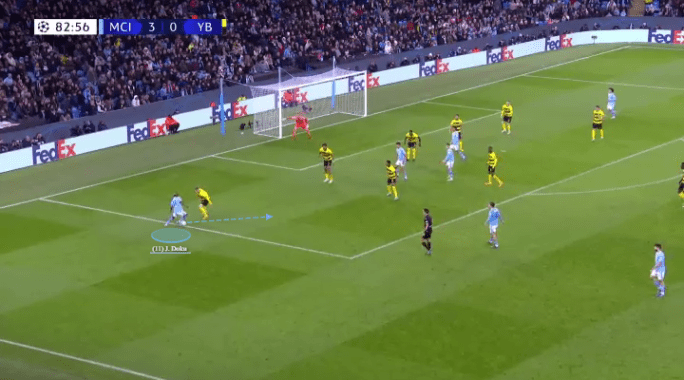

Embed from Getty ImagesIt took about a month, but Guardiola ultimately returned to the tactic in the closing stages of City’s Champions League and Premier League winning run-in. John Stones achieved all the acclaim for his ability to step in and out of midfield, helping City toward better ball-carrying from midfield, and a sound 3+2 rest-defense going the other way.

As it tends to go when Pep Guardiola produces something innovative, other teams were destined to copy. Although, despite all the hype and praise for the centre-backs who made themselves capable of stepping into midfield in City’s system; it’s actually the other facet of this approach that’s been diligently reproduced across the calendar year. That is, the Nathan Aké role.

Embed from Getty ImagesTo some extent, this is nothing new. Bayern Munich played Benjamin Pavard as a right-back for years. Barcelona often used Ronald Araujo or Jules Koundé as a more defensive, inverted full-back to allow the high-flying nature to fully come to life down their left. Even Mikel Arteta, a Pep disciple, prioritized Benjamin White at fullback before Pep well and truly introduced this approach into the City team.

Embed from Getty ImagesHowever, more often than not, these players still held (or still hold) some degree of traditional responsibilities of the modern-day full-back. Ben White for example frequently gallops forward to overlap Bukayo Saka down the right.

It might be an overstatement, but Pep ultimately redefined what it meant to be a full-back in a top-level team (years after already doing so with his ‘Inverted Fullback’ tactic). It used to be only the low-possession teams that would operate with defensive fullbacks. Now, even the best in the world have at least one of their fullbacks holding a defensive stance.

Embed from Getty ImagesAdditionally, what’s truly different about 2023 is the extent to which centre-backs have been utilized in that wider role, operating as a fullback out of possession, and a member of a back-three build in possession. At this point, you can look up and down the Premier League to find this approach being used in nearly every single team.

Embed from Getty ImagesWith that, I assess some reasons for why this tactical shift occurred; why so many managers have taken the same approach all at the same time (is it truly just the Guardiola effect?), and the benefits that this has allowed for the very best teams in the world to continue achieving sustained success.

THE IMPORTANCE OF CENTRE-BACKS

Embed from Getty ImagesAs integral members to the spine of any team, centre-backs are one of the most sought after, prized after positions on the pitch. Every team will want to get the balance right at the back in finding two competent centre-backs to play in that spine. But given their importance, teams will often then stockpile all the top centre-backs they can find. Clubs with an additional European competition will want at least four centre-backs to rotate between and allow those important members some time to rest and recover; and the rise of back-three formations means that those wishing to be flexible enough will usually have even more at their disposal.

Embed from Getty ImagesBut this creates somewhat of a dilemma. While chemistry and consistency are generally seen as important features of a back-line, top-tier clubs have ultimately created a ‘problem’ for themselves within the talent at their disposal. Manchester City’s recruitment of Manuel Akanji is one such example, with the club already having Ruben Dias, John Stones, Nathan Ake and Aymeric Laporte to choose from at the time. How do you fit all of these players into the same team? You play one of them (or two of them) out of position.

Embed from Getty ImagesBut before getting carried away, let’s break down why a team like City would be incentivized to play so many of these players at once. In all of the discussion, this simply has not been discussed enough. It lies within the typical strengths of the modern-day centre-back, where they offer advantages that other players simply don’t possess.

Embed from Getty ImagesModern-day centre-backs tend to be multi-faceted players capable of both playing out from the back and defending with persistent physicality. In comparison to full-backs, they tend to be more capable and comfortable accomplishing brilliance out from the back in their own third, and more prominently, tend to be significantly better 1v1 defenders. This is why a club like City recruited Manuel Akanji in the first place, a superb ball-carrier that had the highest end of pressing and duelling percentages in his final few seasons with Borussia Dortmund.

Embed from Getty ImagesThe level of athleticism and physicality these centre-backs possess becomes particularly imperative in transition, which is something that all the top teams have to diligently assess. These top-tier possession-based teams tend to concede a high percentage of their chances against from counter-attacks or set-pieces, rather than open-play, since they spend so much time in possession of the ball themselves. Having more physical defenders in the back-line massively aids the team’s ability to contend both types of chances. As we’ll come to discuss, it even helps them in possession.

Embed from Getty ImagesThis is the cycle that we’ve seen with many top-tier sides contending with the demands of European football across the calendar year. They recognize the importance of their centre-backs, and the advantages those players offer in comparison to other players. They then recruit more of them, and cause themselves a dilemma in team selection. In fitting more of those talented players into the team and also constructing the right balance within their rest-defense, they’ll then shift one of those centre-backs out wide. It’s the pattern we’ve seen with Aston Villa and Ezri Konsa, Newcastle’s use of Dan Burn, and Chelsea with Levi Colwill. Now clubs are even recruiting players specifically for the purposes of playing that outside centre-back role, such as Arsenal with Jurriën Timber, or City with Joško Gvardiol. We’ve never seen anything like this to the extent we’re seeing in 2023/24.

Embed from Getty ImagesBut it’s worth noting once more that in many ways, these teams end up with a fullback who is better able to accomplish the demands of what the team wants to put together in that position, even though that fullback is actually a centre-back. So with that, let’s discuss the advantages of this approach.

REST-DEFENSE

The 2010s to early 2020s was defined by two general approaches to the utilization of fullbacks. Either clubs would play with two high-flying attack-minded fullbacks (like Liverpool with Trent and Robertson), or one or two inverted fullbacks (like City with Cancelo and Walker). Both tactical implications created a rest-defense within back-four formations that positioned just two centre-backs at the back, complimented by two to three players in front of them. Rest-defense structures of 2+3 or 2+2 were quite common, and had their advantages in counter-pressing central areas.

But teams adopting these approaches (and the likes of Brighton that still adopt this approach), always have issues in stopping counter attacks in the wide areas.

The initial line of the rest-defense can be bypassed by a quick ball out into the wide channels, forcing the two at the back to shift out of position. One centre-back needs to come across in stopping the wide attack, and the other is then forced to shift across to cover that position. The remaining players, as they race back into position, then need to fill gaps that open, rather than adopting their normal positions.

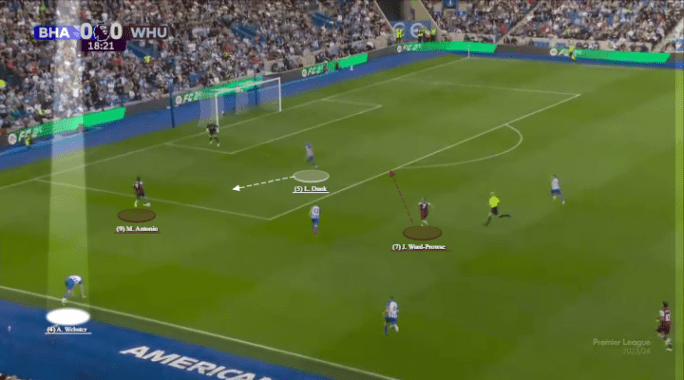

I broke this down earlier in the season when West Ham tore Brighton apart in transition. In the above image you can see the danger of this approach. The first centre-back, Adam Webster, finds himself beaten by Michail Antonio’s strength in the wide area. Now it’s only Lewis Dunk left to cover, and James Ward-Prowse can seek the space on the other side of him. West Ham did this to Brighton over and over again.

For all of their inclinations toward recruiting players that excelled in transition (Rodri, Ederson, Ruben Dias, etc.), this was often the key issue that held Guardiola’s teams from winning major trophies. One of many examples of their tumultuous time in transition came in last season’s 3-3 draw with Newcastle at the start of 2022-23, when Allan Saint-Maximin had a day filled with fun up against Kyle Walker.

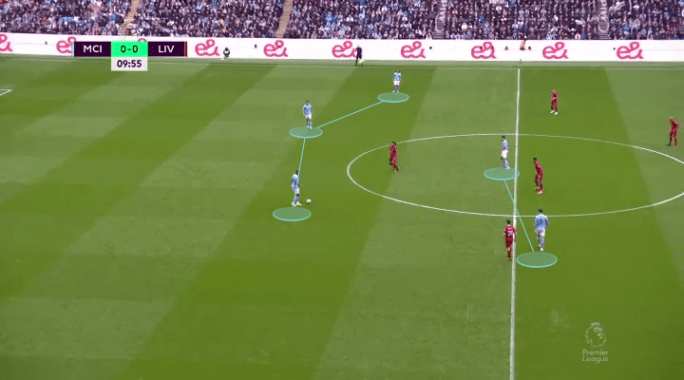

After that, Guardiola might have decided he’d had enough, and changed his approach for the better. As Pep recognized himself, a rest-defense that incorporates a back-three rarely ever has the same issue.

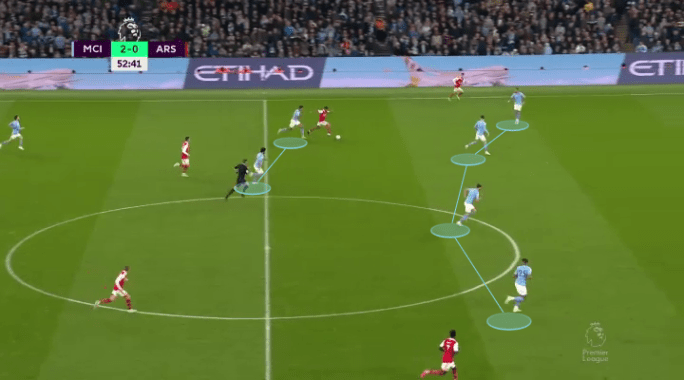

In a 3+2 or 3+1, that level of shifting and position finding rarely ever needs to happen. You immediately have outside centre-backs capable of handling the wide areas, and a sweeper between them that can hold their position. If the first defender finds themselves beaten, the balance of the team does not have to come out of whack, as you still have two more defenders that can close the gaps as the other players race back in. If you’re City, you might even have a central midfielder immediately dropping to create something even sturdier.

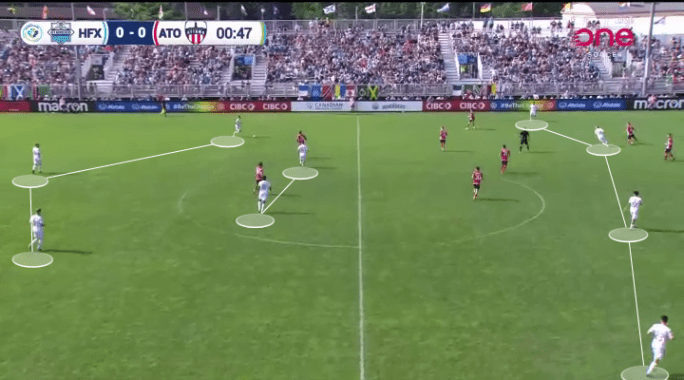

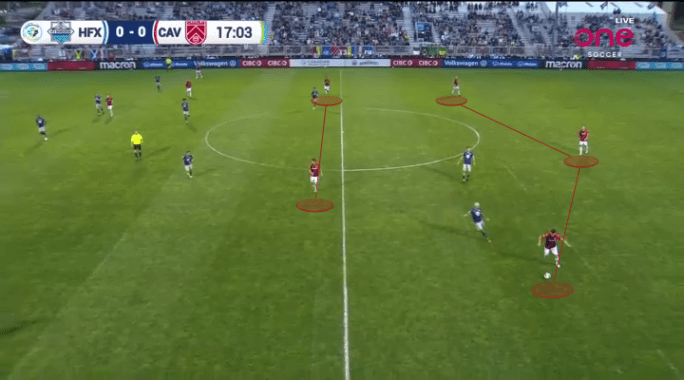

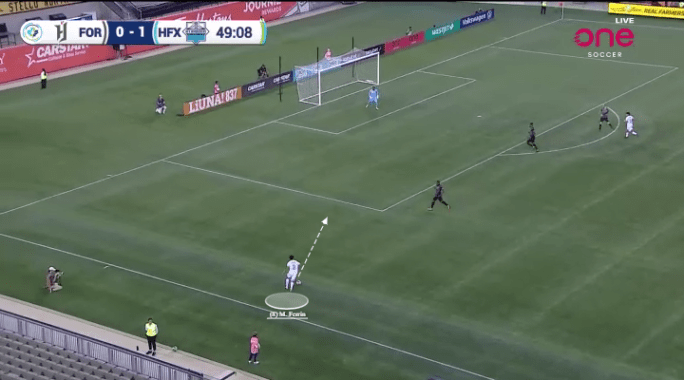

With this in mind, the back-three build has been key for the ability of the top teams in the world to achieve a better rest-defense. But it doesn’t necessarily explain why a centre-back has been used in that role rather than a full-back. Why not just have a full-back play that defensive role in the back-three build? In actuality, some teams, like Canadian Premier League club HFX Wanderers, even did take that approach.

Rare exceptions aside like the already brilliant transitional pace of Kyle Walker, the advantages to having that player be a centre-back outweigh the potential benefits of a typical full-back fulfilling the void. Due to their typical size and build, centre-backs are more easily able to combine the athleticism and agility that full-backs offer, with a greater degree of physicality, height, and strength. This often makes them superior 1v1 defenders, and more easily able to handle transitional moments or tricky dribblers out wide with poise and composure.

Embed from Getty ImagesModern day full-backs on the other hand have developed with other modern trends of contributing to attacking phases and holding more of an importance in the opposition’s half. Additionally, while many of them are brilliant ball-players, they’re also smaller, and less accustomed to playing out from the back in the typical central channels that centre-backs have become comfortable completing.

Embed from Getty ImagesWhen Liverpool started to use Andrew Robertson in the role as a reserved left-sided player in their back-three, much of the argument for why it didn’t make sense was that he “wasn’t a centre-back”. The more polished way of making that point is to say that he lacks the same level of physicality as Levi Colwill, Dan Burn or Ezri Konsa; and hasn’t yet established the muscle memory of knowing exactly what steps to take in-possession from that kind of vantage point.

So all ends up, it’s started to make more sense having Nathan Aké, Josko Gvardiol or Manuel Akanji play wider out of possession, so that the team can have greater advantages both in building out from the back, and then defending when the ball changes hands. The other reason why it makes so much sense is within the construction of balance.

STRIKING THE RIGHT BALANCE

Alongside the recognition of what allows for a better rest-defense, most modern day clubs still want to utilize a high-flying wing-back in some capacity. They’ve spent years recruiting the best chance creators they could find, and still want to allow those creative players license to roam forward and contribute to attacks.

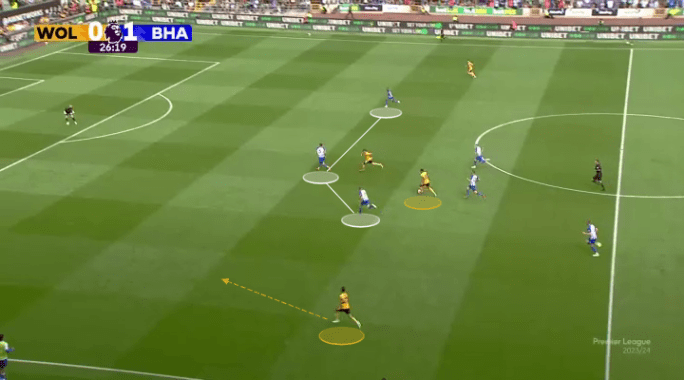

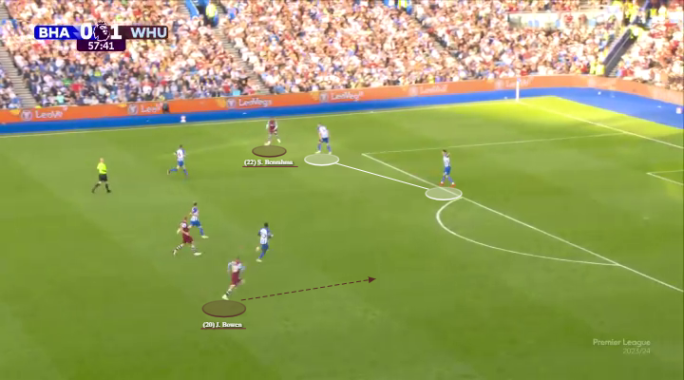

Embed from Getty ImagesBut they no longer want both full-backs to have an attack-minded or possession-focused build-up role at the same time. Again, it’s not necessarily new for one full-back to advance forward as the other stays put. But what is more specific to 2023 is the degree to which players are being assigned clearly defined roles as either the attack-minded full-back in the team, or the defensive, inverted one that joins the centre-backs in possession. Take Chelsea for example with Malo Gusto flying high on the right, and Levi Colwill staying deep on the left.

Embed from Getty ImagesCity’s approach is slightly different within the maintenance of that back-three build, positioning a centre-back in midfield rather than utilizing a high-flying wing-back. They remain a bit of an anomaly in that approach.

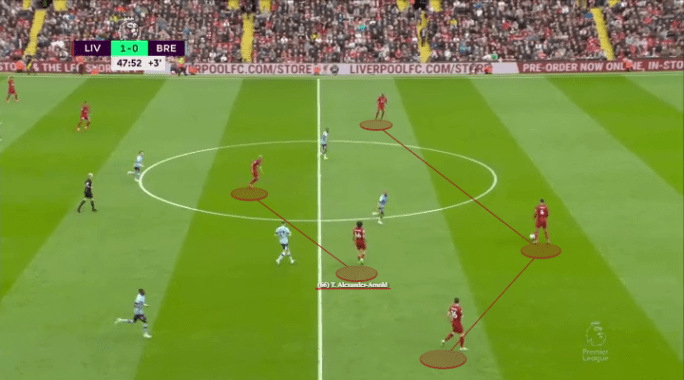

Embed from Getty ImagesMost others create this shape in order to have better balance across the entire pitch. One fullback that’s more defensive and one that’s more attack-minded also means they can achieve a fun balance in the wide areas with their wingers. These teams will now position their most creative player on the side of the wing-back, allowing that player to drift inside and play as that ‘Inverted Winger’ in the half-spaces. Down the other side, they’ll have a more ‘Direct Winger’, injecting more pace and power. You’ll then have this sort of 3-2-4-1 attacking formation come to life, with a diamond quartet that can combine in central channels to break down opposition blocks.

Even though City adopt a different approach to these other teams, they utilize that same 3-2-4-1. They just do so with wingers that tend to stay wide, which is something Guardiola’s prioritized since entering the Etihad.

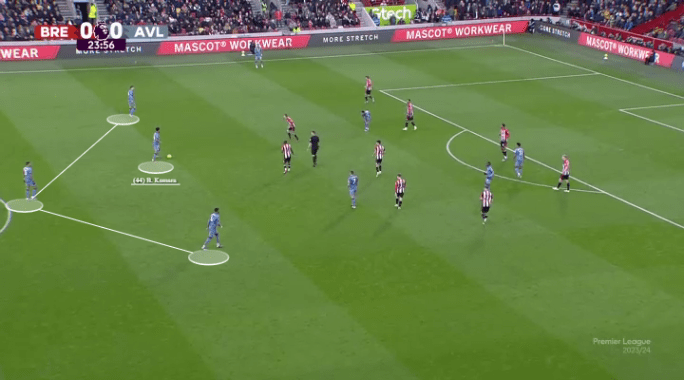

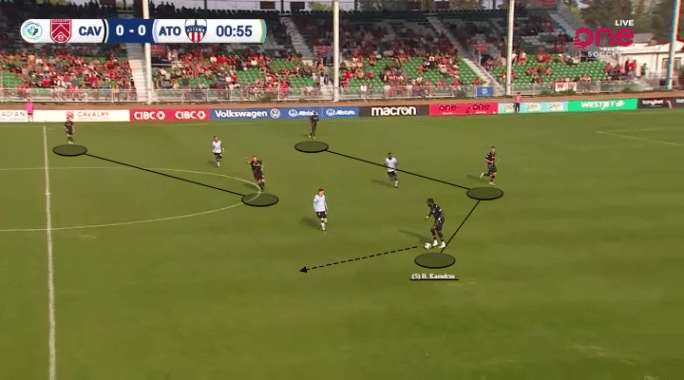

With clearly defined roles spread across the pitch and players that offer different elements toward the balance of the team, these teams are achieving more success on the hunt toward trophies. Deep-diving into my own home country, the Canadian Premier League’s regular-season champs (Cavalry) and surprise package (HFX Wanderers) achieved by far the best balance with what they conjured up in 2023. Both operated with this 3-2-4-1, in exactly the manner prescribed. HFX took the more unconventional approach in positioning a more creative fullback in that left-sided role more often (Wesley Timoteo), but Cavalry took the same approach as Man City in operating with a physical, ball-playing defender (Bradley Kamdem).

These same teams had great balance going forward with their most creative player pushed inside from the right-half-spaces (Aidan Daniels for HFX and Ali Musse for Cavalry), and a more direct player down the other side (Massimo Ferrin and Goteh Ntignee).

In creating a winning team, striking the right balance within the eleven players on the pitch is always an essential piece to the puzzle. Operating with a centre-back at full-back has been critical to allowing these teams to strike better balance across the pitch. And not just with their rest-defense; and not just within that single position. The knock-on effects are being seen around the pitch.

Embed from Getty ImagesIt might be wrong to credit this tactical approach to Pep Guardiola. After all, the origin story to the ‘fullback’ is because the defender was fully back. However, in operating with a centre-back that steps up into midfield, Guardiola also created a construction within his team that regularly positioned centre-backs out wide. From then on, this approach has only become more popular. It’s been the top tactical trend of 2023, and often one that’s allowed the best teams in the world to thrive.

Embed from Getty Images

Thank you for reading my musings across the year. It’s been a big year for TMS and more exciting things are sure to come in 2024. Be sure to check out more of my articles and follow on social media @desmondrhys to never miss a beat. Thanks again.

Chaos vs. Control: A Collision of Principles

Some like to approach games in a disciplined structure, intentionally and meticulously dictating games to their own tempo. Others opt for a more emotionally-charged philosophy, reliant on the belief, energy and willpower of their trusted eleven on the field.

Game of Numbers #37 – Forge FC’s use of centre-backs in midfield like Manchester City

For the unfamiliar, Forge FC are the Manchester City of the Canadian Premier League. They play a possession-based 4-3-3, stacked with ball-savvy savants, and a culture that embodies winning. The Canadian Premier League’s been around since 2019 now. Forge have won the Playoffs in four of the five seasons, and lost the final in the…

Comparing the Canadian Premier League’s next best centre-forwards

The best strikers in the modern era are able to combine a vast array of skillsets. We’ve seen this play out in the CPL this season, with those unable to fully combine all the necessary skillsets also failing to turn their talents into goals. Here is my analysis of four of the next best centre-forwards…

Discover more from TheMastermindSite

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.