As coaches, the vast majority of us want what is best for our athletes. But there still exists a never-ending divide between what is deemed more valuable by the standards of today, as opposed to the ways coaches learned in the past. Modern-day coaches will emphasize fun and enjoyment through games, and old-school coaches will emphasize “hard work and resilience” through repetition.

In reality, both can be blended together.

Repetition is a beautiful thing. But it’s a beautiful thing that can be taught in the context of game-realistic scenarios without over-complicating matters for players. It’s also a beautiful thing that is best developed away from team environments, when athletes are participating in unstructured play or 1-on-1 coaching sessions. It’s also a beautiful thing (I’ll stop before I become a Harvey’s commercial) that needs to be brought back into the context of the game.

The argument of “How did Lionel Messi get so good?! He practiced dribbling for 107267,000 hours!!” might be true. But I’d guess many of those hours came in his own home environment, out on the streets, in the yard, in the school playground, on his own and with his friends.

When you then put that player into a team environment, why would you not then take advantage of the fact that Messi now has teammates to actually practice his dribbling against? Repeating one of my favourite lines from this article on coaching individuals, the best technical wizards never made it to the pros.

Why? Because they were never able to connect how those techniques translate to the game. I guarantee you there is some random person out there who can dribble better than Messi. But I guarantee you that person has no idea what to do after he beats ten players and the chicken crossing the road.

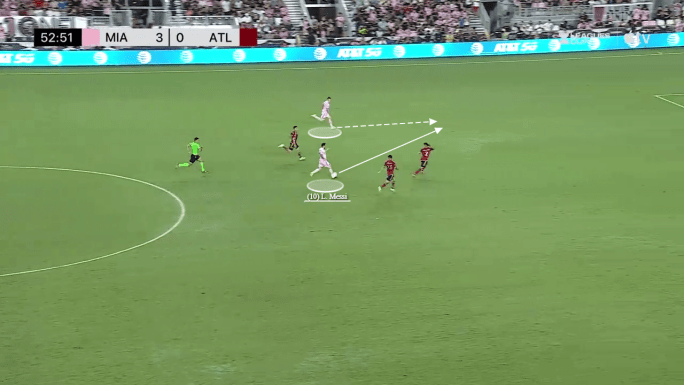

Lionel Messi does not need to develop repetition around dribbling through the use of cones or 1v0’s. If he wasn’t an alien from outer space, he’d instead need to develop repetition around dribbling under pressure. By the way, that’s how Messi got so good at dribbling. It wasn’t those 107267,000 hours of unopposed dribbling. It was those 107267,000 hours of opposed dribbling, many of which probably came in an environment that he enjoyed, without any coach dictating him to dribble in a certain way or to do a certain skill.

Embed from Getty ImagesContext is key. I’ve done many activities in 1-on-1 environments where you virtually don’t have any other option than a pylon. When it comes to complicated skills that players have never done before, it’s best to practice the skill in an unopposed format first, so the player can then do it in an opposed format. I’ve spent hours helping players develop fancy-dance skill moves over a laptop that they would have never pulled off had the older sister walked in and kicked the ball away. But I’ve never seen one of those players use one of those skill moves in a game.

Rainbows are cool, but other than in She’s the Man, have you ever seen someone do one in a game?

How many times have you taught players all these fanciful skill moves to use in practice through isolated dribbling “drills” that they never use in games whatsoever? Why is that the case? Because you never created a link between how to accomplish that skill within the context of a real game situation. You only allowed the player to accomplish the skill in isolation.

Embed from Getty ImagesThis is why sporting bodies of today harp on deploying a games-based approach. It’s not meant to devalue or de-emphasize repetition and skill development. It’s meant to increase repetition and skill development in the context of a game, and to decrease repetition and skill development in ways that don’t apply to the game.

But as they would say – ‘you can’t do the skill in a game without first practicing the skill unopposed/isolated.’ To some extent that is true. But coaches adopting this mentality often forget what skills players actually need to develop to play sports successfully. They don’t need to spend hours on corner kicks. They don’t need to spend ten minutes doing push-ups and suicides. They don’t even need to spend five minutes passing back and forth to a partner or dribbling through cones. I’m already bored, and I’m so much less likely to work hard.

After U3/U4, players have the motor skills to be completely capable of passing while moving. It’s great to have U17/18 players practice the act of passing through isolated techniques like passing back and forth to a partner, but they’ve moved far beyond the need for that basic repetition. They need to develop repetition around the real demands of the game. They need to develop repetition around playing passes under pressure. They need to practice how to perceive the right moment to actually make that pass, as opposed to when the better time might be to dribble, carry, pause, shoot.

They need to develop repetition around perceiving what the best passing option is in the moment based on their perceptions of BOTS. Now they can’t pull off that amazing switch of play? Now let’s practice that in isolated training through a one-on-one coaching session, through homework in their own environment, or through game-realistic scenarios that allow players to practice not only that switch of play, but what happens afterward.

Embed from Getty ImagesBy the way, when we’re speaking about young players, the complete inability to pull off a long switch of play is less likely a technical problem and more a muscular capacity “physical skill”. Give them two years while developing short passing techniques, and they will arrive to your destination.

Besides, if coaching an U9 team, I don’t need to help players develop their long-passing anyway. Instead of lambasting my players for not being able to switch a long diagonal from point A to point B, I might recognize that the field of play they actually use in games is 25-metres wide. Suddenly, my players can actually pull off “long passes” if they’re put into the context of the field they play on.

Embed from Getty ImagesYou need to be aware of the demands your players actually face in games, and replicate those scenarios in training. The demands they never face in games are not the ones they need to develop repetition around. As I said to a horseback rider recently, you don’t get better at riding horses by riding zebras.

There might be some benefit to riding that zebra that you could apply to the horse, but you know where you can get a 100% direct correlation? On the horse.

Embed from Getty ImagesIt’s not “too complicated” for athletes to do this. It’s so much easier.

I’ll give you another example thrown my way:

- Players in a baseball practice hitting a baseball on a tee.

Awesome. Great for the act of repetitively practicing the art of a bat swing. By a few seconds, you’ll probably get more repetition by having the next ball ready to be placed on the tee, as opposed to an actual pitcher tossing you the balls.

Embed from Getty ImagesBut beyond those seconds, what are the gains? Do you play with a tee in baseball? Do you stay at home-base after hitting the ball to lean over, grab a ball, and hit another one? Do you hit a ball at the exact same height with every pitch?

So why not have your mom pitching you the ball? Mom just wants to be involved, dad.

Have mom act as the pitcher, have her toss you a ball (which will naturally be at slightly varying heights), and develop repetition around hitting the ball, and what you’re going to do afterward (run to first base). This is what we need our athletes to develop. It’s not too complicated for athletes to do that simple action without having first practiced hitting the ball on the tee.

Embed from Getty ImagesIn fact, I’d go as far as to say that you are actually “simplifying” that action, by having players be able to see a clear connection between practice and game. It’s far more difficult for the basketball player to recognize patterns in a game when they are suddenly in front of a defender, when all the technical prep they’ve done in training has been without a defender.

Adding a defender in training is not “complicating” the exercise (complicating is good by the way. Sports are inherently complicated). It’s simplifying the exercise because it’s preparing athletes for what they are actually going to face in the game.

It’s cool to spend 10,000 hours dribbling a basketball because some guy from the 1800s said it would help you master the skill of dribbling a basketball. But do you actually want to master the skill of dribbling a basketball? Or do you want to master the skill of dribbling a basketball against opponents in a game? This goes for all sports.

Skating clinics will make you a better hockey player, running exercises will make you a better soccer player and riding a zebra might make you a better horseback rider. But why waste time in a team practice environment having players go through those motions if it doesn’t apply to the demands they’ll face in their sporting event? Other than riding the zebra, it’s not even fun.

“BUT HARD WORK ISN’T FUN.” That’s the other argument of this debate when it comes to the old-school ways of thinking. They say – hard work isn’t fun. It’s the feelings after that hard work that are fun. Winning is fun.

Embed from Getty ImagesThat’s true, winning is fun! Might be difficult to win if you spend more time on the height of players’ socks than developing pattern recognition for the game, but I guess I don’t know much.

If you want players to hate baseball because they never actually got to play baseball, you can be one of the coaches that helps athletes quit sport before the age of 13. But if you want your players to enjoy their experience within the frame of hard work, there’s nothing harder than having to put all the skills they learned into the context of a game.

Listen to your players when they’re asking if they can “scrimmage”. They might know something (actually they do, they know what’s actually fun for them). More fun = more learning = more longevity in the sport = more development = more likelihood to win, turn pro, etc.).

I’ve heard these same old school coaches bemoan that they’re players don’t want to do anything. “The hardest part about coaching these days is that players don’t want to do anything!!” If you inspire the right mentalities, a positive team culture and find a way to connect with each individual, you might be surprised about how many athletes are willing to run through a brick wall for you (just don’t actually ask them to do that).

But if you’re persistently doing activities that are not fun, you’re not fostering learning. You’re instead decreasing their love of the sport, which will eventually stunt their learning altogether.

Embed from Getty ImagesThat’s why those 1-on-1 contexts are so powerful. You can develop skills for players that need it when they want more, without making the other athletes hate sport because they’re being asked to skate in circles rather than play the game. There’s a reason I enjoyed skating in circles at dedicated skating clinics more than at practice. There’s a reason why it was more valuable for me as an U4/U5 skater just making my way downtown.

It’s true, I got significantly better at hockey from one year to the next because my parents put me in a load of hockey camps each summer. I also hated every second of those camps, wanted to be at home (where I likely would have been playing hockey anyway!), and was likely less motivated to perform at my best in developing those skills at those camps. I quit hockey by the age of 13.

On the note of “getting better”, I also would have improved if those same camps enveloped a games-based approach. That’s where real learning happens – when athletes can see their own decision making and technical execution come to life in different moments in a match and think about what they did well, and what they would do differently next time.

Embed from Getty ImagesI didn’t learn how to shield a hockey puck from isolated 1v1 scenarios. I learned how to shield a puck in hockey from the pressures of penalty kills in games. If we can replicate those exact same demands in training right from the start, why wouldn’t we?

Ask me – What are my favourite hockey moments? Playing games, scoring goals, having a coach that cared about me, and playing hockey in my basement through unstructured play that felt meaningful to me.

That’s how I got better at hockey too. I played the sport on my own in a way that was fun for me, and then I took those learnings back into practice and games. I played a ton of hockey games, and I scored a ton of goals.

Had I been put in environments centered around small-sided games where I could constantly compete and score a ton of goals, I might have enjoyed my hockey experience more. I might have wanted to attend those camps and I might have actually worked harder. I might not have quit by the age of 13. I might be in the NHL right now. So where did that money on technical hockey camps really go? Did it go to my learning? For a few years. But not for the long-term.

Games-based learning is about emphasizing long-term athlete-development.

Embed from Getty ImagesI’ll end with one final example. As a runner, we often do “drills”. These drills are meant to work on running form (the biomechanics of the arm swing in particular). In the context of a warm-up or cool-down, they can activate the muscles in a more gradual way than sprinting right out of the car. But you know what else helps with running form? Running. You know what else helps activate the muscles gradually? Running. What am I going to be doing when I’m racing? Running.

I could do high knees, but I think I’d come in last, and tire myself out after a kilometre.

Practicing running form and mechanical efficiency while actually running will lead to more long-term gains than drills. It’s also more translatable to a race, and DING DING DING – you guessed it – more FUN!

At the same time, there is only so much running you can do before you get injured. So if you then what to supplement that running with “drills”, that’s when you do it. You do it in the warm-up, you do it in the cool-down, you do it through university campuses and suddenly a whole flock of students are mocking the way you’re marching around town (that was fun). It’s not like you never do drills to work on mechanical efficiency. There’s a time and a place for them (clearly not university campuses).

But if you want to actually get better at running, and enjoy running to a place where you can sustainably get better at running, go out and run.

Or ride horses, or play baseball with mom. Repetition is valuable, but not at the cost of fun, not at the cost of putting that repetition into the game itself, and not at the cost of long-term athlete development.

YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY…

Game of Numbers #39 – Erling Haaland’s backstep before goals

Manchester City have scored 15 goals in the Premier League’s opening 8 matches. Erling Haaland has scored 11 of them. And among many of those goals, a common trend has emerged. I call it – the backstep!

How to Become a Football Coach: FA Coaching Certificates & University Pathways

Discover how to become a football coach in the UK, from beginner to the pro level. Explore FA coaching certifications, university programs, and how to start—even with no experience.

Best Formations for 9v9 – Ebook

9v9 is one of the most exciting stages in the development of young players and can often be the first time they are truly able to understand positioning, formations and how to play to the strengths of their teammates. This Ebook gives coaches an opportunity to learn all the in’s and out’s of coaching 9v9,…

Discover more from TheMastermindSite

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “Why games-based learning leads to more long-term gains”