This article is part of our ‘Introduction to Football Analysis’ course. See more information and take the course for $59.99.

Chances are, if you’re getting into tactics and analysis, you’ve heard the word “phase” or “moment” to describe the events that transpire across a football match. But what are these so-called “phases”? As part of our Intro to Football Analysis course, we break it all down. Here is everything you need to know about the various phases of football, and how compartmentalizing the game in this manner can allow you to achieve greater success in your analysis.

THE FIVE MOMENTS OF THE GAME

While this may seem rudimentary, the first step to breaking down the game is to differentiate between “attack” and “defense”. When a team has possession of the ball, that is to be considered their “attacking phase”, regardless of where the ball lies, or attacking intent. When a team does not have possession of the ball, that is their “defensive phase.”

Embed from Getty ImagesDepending on the third of the field that the situation encapsulates, the game can then be broken down into multiple sub-phases of “attack” or “defense”. But first, we must provide one other specification. The “attacking phase” and “defensive phase” only start after the team has accumulated enough time to properly set themselves up in their shape and structure, and allow their principles to take center-stage. Otherwise, the situation is considered a “transition”, either from attack to defense, or defense to attack. This encapsulates the five to ten seconds of time from either a regain or a loss of possession.

Here we see that the game can be broken down into four key “phases” or “moments”.

- Attack

- Defense

- Attacking Transitions (defense to attack)

- Defensive Transitions (attack to defense)

You might wonder, ‘why are transitions their own phase’? That’s down to the fact that transitions (particularly att. transitions) rarely have more than a set of practiced principles that guide the team’s methodology. There are rarely intended shapes, structures or even patterns that occur between different moments of transition, instead principles that the manager wants to bring out (i.e. forcing wide, closest to the situation intensely and immediately pressures the ball, verticality, etc.). This makes transitions the most inherently difficult element of the game to dissect, particularly in trying to establish patterns. But that is inherently why they are worth further scrutinization, particularly through their unique differences to the other moments of attack and defense.

Compartmentalizing the game in this manner allows us to provide substantiated analysis that can be clearly communicated to an audience. We can use these phases to break down the different elements of a team’s tactical plan, rather than creating a jumbled mess as we jump in between the phases in uncoordinated fashion.

But wait, don’t order yet! There’s more. Not only does each phase have its own set of sub-phases depending on the third of the pitch, BUT we also can’t forget to add in set-pieces. This is particularly imperative when conducting opposition analyses for pro clubs, as they will always want to understand how the other team handles and responds to set-piece situations.

You can then add a fifth category to the footballing analysis recipe for success.

- Attack

- Defense

- Attacking Transitions (defense to attack)

- Defensive Transitions (attack to defense)

- Set-Pieces (both defensive and attacking).

Memorize these five phases. While each coach and each analyst may have different ways of seeing the game, this is the most common way of breaking down the game into different parts. Even those that would classify transitions or set-pieces within the umbrella of the “attacking” or “defensive” phase recognize the importance of providing specific information about tactical plans within these moments.

Now, before moving on, I want you to reflect on your own experiences, practice and knowledge. What phase of the game do you feel as though you have the greatest gap in knowledge and understanding? Remember, I’m here to help you on your path toward analysis expertise.

As we move along in this article, I want you to pay close attention to all phases. But I require you, as an absolute must, to ask questions and take detailed notes on the phase in which you’ve referenced above. The unfamiliar can be painful, but we must be willing to step outside our comfort zones.

So now that we’ve established the five key phases, let’s finally dive into how these phases are broken down between the ‘thirds’.

THE THIRDS OF THE PITCH

Before breaking down these phases in greater detail, we must first understand how the game can be divided across the pitch. It’s true that Guardiola, Cruyff and various others have different concoctions for how they separate different areas of the pitch. A widely used formula to breaking down the pitch into sections is taken from the work of Grant et al. (1998), as part of an analysis of the 1998 World Cup. The premise was essentially that teams should be looking to play the ball into “Zone 14”, which lies just ahead of the penalty area. Football Performance Analysis breaks this down nicely in their article about “Zone 14”, again – the zone in which all footballing teams should be striving to control and invade.

In the above image, you can vaguely see the pitch broken up into thirds via vertical channels, but not horizontally. So for now, forget about this diagram and the somewhat randomness of the numbers. When we speak about the “thirds of the pitch”, we are referring to the horizontal channels.

Each team has a first third and a final third depending on the direction of their play, and then a middle third that is shared between the two teams. As you can see from the image, the team in possession (the red team) has their final third at the far left of the pitch, and their first third at the far right of the field. But it’s the exact opposite for the white team, attacking the other way. To help break apart this discrepancy, the first third is often called a team’s ‘own’ third; and the final third is often called the ‘opposition’s third’.

These thirds are particularly imperative to analysis in football, as different teams will set up to attack and defend in different ways across these three sections.

Embed from Getty ImagesAs an example, Thomas Tuchel’s Chelsea will typically defend in a 3-4-2-1 high up the pitch in the opposition’s third, with their wing-backs putting pressure on the wide areas as soon as the ball is played down the left or right. Lower on the pitch, the team will then float into a back-five, resembling more of a 5-4-1 to 5-2-3 in their own third, whilst maintaining a sense of rigid compactness as they shuffle and shift with the play.

This is why the game is broken down into thirds rather than just halves (i.e. one’s own half and the half of their opposition). Phases of pressing from the front and playing out from the back tend to look very different from other phases, and so we’d be remised not to break it down further and describe these situations as single entities.

We’d also be remised not to mention the way that analysts typically divide the game vertically between five channels: two wide channels, two half-spaces, and the central channel.

Understanding this allows us to better gauge where a team looks to progress and funnel their play both on and off-the-ball, in and out of possession.

So now that we’ve established the thirds of the pitch, let’s describe each “phase” in detail. We want to understand the game on a deeper level not for purposes of raising eyebrows, but for purposes of simplifying the game for the players and coaches we strive to serve.

ATTACKING PHASE

The attacking phase involves the time of circulation, possession, and attacking intent within the boundaries of having time to set up tactical plans and strategies for success.

If you’ve read any of my Game Model Examples, you will already know that the attacking phase is broken down into three parts, based on the third of the pitch. In the first third, we use the term “Build-Up” to describe the way in which the opposition moves the ball and sets up to beat an opposition’s press.

This can range from the meticulousness of Pep’s ‘Inverted Fullbacks’, all the way to the non-existent build-up of Sean Dyche’s Burnley. Regardless of approach, every team has some sort of build-up phase, whether that involves getting the ball up the field as quickly as possible, or combining with short, one-and-two touch passes.

When conducting opposition analyses, we want to understand this phase like any other, so that we can counter-act it.

Next on the docket is the ‘Progression’ phase, which involves the team’s ability to progress up the pitch and play the ball around the middle third.

If they are not able to progress into the final third, they may circulate the ball or even recycle play back into the ‘build-up’ phase. But the ‘Progression’ phase is where teams spend the bulk of their time in possession, and therefore must be scrutinized in intense detail.

The final stage is that of the ‘Creation’ phase, which involves the team’s methodologies for creating chances and scoring goals, particularly as they get closer to goal (i.e. in the final third of the pitch).

This phase is sometimes referred to as the ‘Finishing’ phase in certain cultures, but the term ‘creation’ is used around the world more prevalently. Given that this phase is where the magic happens, it becomes particularly imperative to explore.

So now that we’ve broken down the attacking phases, let’s ensure you get the idea.

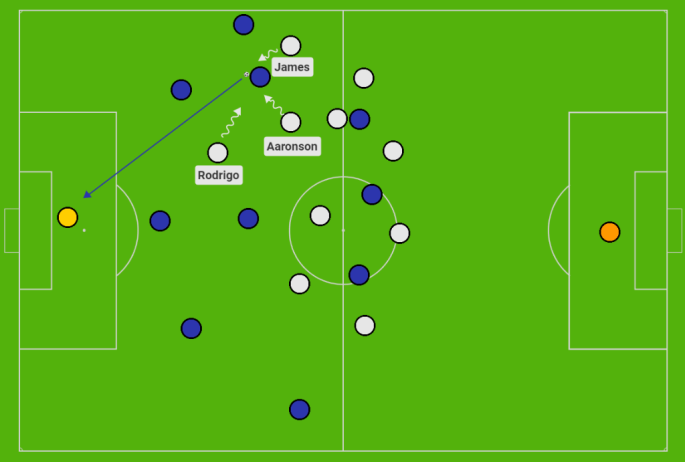

PRACTICE: CAN YOU RECOGNIZE THE PHASE?

It’s crucial to recognize that while the “attacking” phase may be the easiest to notice and postulate about, we must strive to create balance in our analysis. Most “tactical reports” pay very little attention to the other phases. That’s because the camera only wants you to see what’s happening on the ball (i.e. the in-possession moments for both teams). It takes a special person to train their eye to see what’s happening away from the ball, and focus attention on the other phases too. This isn’t to say that the “attacking” phase fails to warrant attention; just that we must be careful to not over-produce in-possession moments within our analysis without providing the entire context.

DEFENSIVE PHASE

The defensive phase encapsulates the time in which the opposition are able to set up shop, find their shape and shift with the play off the ball and out of possession. Like the “attacking phase”, it is also broken down into three components based on the third of the pitch. Before detailing the three sub-phases, it’s important to note that the terms are often used interchangeably in analysis to describe a team’s over-arching defensive style. While a team may have one area of the pitch that they prefer to engage the opposition and spend most of their time, every team has moments where they defend in all three sub-phases.

When the team defends high up the pitch, this can be described as their “High-Block”. The high-block incorporates a team’s ability to press from the front (such as in a ‘high press’), but that is not the only consideration to defending in the opposition’s third. It’s true that the ‘High-Block’ closely encapsulates pressing, but it also recognizes that not every team will defend with the same vigour and intensity.

When the team defends in the middle third, this can be described as the ‘Mid-Block’. As you can probably guess from our description of the ‘Progression’ phase, the ‘Mid-Block’ envelops the most amount of time. It is also the most common ‘line of engagement’. That is, a slight majority of teams will allow the opposition to play out from the back and circulate the ball between their less-dangerous members. They prefer to stunt play in the middle of the pitch, so as to not allow the team an easy route of progressing to the final third. By holding shape and not vigorously stepping out of position, the opposition will then have very few routes to go through, around or over the defending team.

Finally, when defending in one’s own third, the moment of time is described as the ‘Low-Block.’ Again, the term is often used interchangeably as some sort of marker for teams that either ‘park the bus’, or have very little attacking intent in their limited possession. A ‘low-block team’ would be one that gets numbers around the ball and narrows the field, with little regard for defending higher up the pitch or even creating longer spells of possession. But every team defends in a low-block at some point in every single match, even the ones that keep upwards of 60-70% of possession. This is because this is not a style of play, but simply the way of describing what a team accomplishes when they defend in their own third, close to their own goal.

With these descriptions in mind, let’s practice!

While it’s not entirely ‘taboo’, I would urge you to stop describing teams as though they only defend in one specific ‘block’. It depends on the positioning of the ball in that moment, in that third of the pitch; and can fluctuate in a matter of seconds. It’s certainly acceptable to say that your team had trouble “breaking down a low-block” or “beating a high press”, but it becomes less acceptable when you say something along the lines of “the opposition defended in a high press” without any recognition for the variability between phases. Instead, recognize the area of the pitch, the third of the field, or the moment of the game, and then explain how the team pressed in those moments.

ATTACKING TRANSITIONS

As already noted, attacking transitions are the most difficult to study, as an ever-changing entity that rarely stays consistent. Instead of patterns, shapes and structures, you are typically only able to witness a broad set of characteristics and principles, that may occur in specific situations depending on ball, opposition, teammates and space. If a team tends to edge toward being a “counter attacking team” you may be able to witness more specificities that have been clearly ingrained through careful training. But even then, this phase tends to last a maximum of ten-fifteen seconds. Anything more without a clear chance on goal, and it’s just a normal attacking phase. That makes it all the more difficult to study, as you’re trying to pick up on patterns that exist for nothing more than a fleeting moment.

Nevertheless, transitions are crucial to the modern game, and should be deeply ingrained into training. With my teams, I always emphasized that the moment we win possession, we want to find the quickest route to goal possible, whether that be passing, shooting, or running with the ball. Verticality remains crucial to the process for a successful, goal-oriented counter-attack.

But some teams may also choose not to counter-attack whatsoever, preferring to keep possession and build closer to goal over time. Other teams may counter-attack when possession is won in the final third, but opt to recycle play when possession is won in the middle third. This is why it is again imperative to break down the game into the different phases between the thirds, allowing for a more complete and detailed account of the variability that can occur on a football pitch.

See more….

-> Game of Numbers #4 – Counter Attacking to Score Goals

-> Counter Attacking and the Death of Tiki-Taka Football

-> How to counter attack like Jose Mourinho’s Tottenham

-> Attacking Transitions – The Basics

defensive transitions

You may see slightly more principles in place around defensive transitions, but even they remain heavily fluid and impacted by elements of ball, opposition, teammates and space. Typically, teams leave a certain amount of players behind in their attack, creating what’s called “rest-defense”. Understanding this gives us a clear picture of who must respond to the defensive transition in bailing the team out of danger, and the shape in which those players will cover. Typically that involves what I call “the box rest-defense” of central compaction in a 2+2 shape.

Space can then be exploited wide. As members of that boxed-in quartet shift wide to pressure, new spaces will open in the centre. But the best of the art at reacting to moments of transition are usually excellent in recovering shape or position within those first five to ten seconds. Either that, or they counter-press at the front-end of the pitch extraordinarily well – meaning they put pressure on the opposition immediately after losing the ball rather than falling into their defensive shape.

But again, it’s worth noting differences that may occur between the thirds. A team may counter-press when possession is lost in their build-up, due to the proximity toward goal. But that same team may choose to fall-back into shape when they lose possession in their ‘progression’, rather than relentlessly pressing. Nothing can be taken in isolation, without providing the entire context.

Besides, one of the greatest tests of any capable modern day coach is their ability to adapt to moments of transition, and set up principles that allow the team to achieve success within those transitional phases. A fair percentage of goals are scored shortly after regaining possession, and so it remains a crucial facet of the game for both coaches and analysts alike.

See more…

-> Why Dortmund are so bad in defensive transitions

-> Defensive Transitions – The Basics

SET-PIECES

Embed from Getty ImagesHistorically, set-pieces have been an under-utilized and under-studied tool. More and more, clubs are recognizing the importance of having set-piece specialists on board, and in spending dedicated time on training routines.

At the youth level, I will always proclaim it to be a waste to focus on set-pieces over other elements of the game. You want to develop players, not set-piece routines. But there’s no denying that even at the youth level, a fair share of goals are scored and conceded from free kicks, corner kicks and throw-ins. As a result, it must always be a consideration, and perhaps can be meticulously worked into training via the method of restarting play, rather than having players stand around and practice coach-imposed routines.

When it comes to set-pieces, we’re primarily referring to corner kicks, free kicks and throw-ins. You’d think I wouldn’t have to specify, but I actually find that this is the most eye-brow raising term of all the basic elements to football. Penalty kicks can be incorporated into this bracket, but less so in studying the specifics around tactical set-ups and nuances. Goal kicks and even the kick-off itself can also be considered ‘static play’ and fall under the umbrella of set-pieces.

We choose to include goal-kicks under ‘Build-Up’ (and then ‘High-Block’ when considering the opposition’s perspective). But more teams are seemingly developing routines around kick-off for not only keeping the ball, but scoring goals from the first whistle.

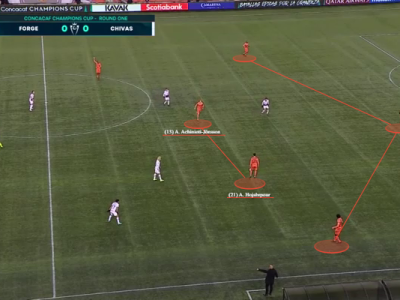

But overarchingly, when analyzing set-pieces, we are looking for patterns that occur over time, particularly in the players that are involved vs. uninvolved, and the areas of the field the team look to target with passes. Capturing this information can allow us to understand how to overcome the opposition’s set-pieces and achieve success within our own routines.

The troubling thing is that sometimes set-pieces can only even be used once before the opposition identifies the tactical plan. This constantly pushes teams to evolve their set-piece plots, and even in some cases develop ‘set-piece specialists’ both from a playing and coaching perspective within the club.

See more…

-> A short corner routine that will guarantee goals (ft. KC Current)

-> A brilliant set-piece routine that will guarantee goals (ft. Cavalry FC)

-> How not to defend set-pieces (ft. HFX Wanderers & Cavalry)

-> Why there’s an abnormal amount of centre-backs taking set-pieces in the NWSL

-> A set-piece routine that will guarantee goals

CONCLUSION

Compartmentalizing the game will only help you to expand your footballing knowledge, and as weird as this may sound, will only simplify the process for your players. By understanding the way the game can be broken into “attacking” and “defensive” phases, followed by the thirds of the pitch, we can better construct our analyses, and allow our players to grow in their understanding about the beautiful game.

So there it is! How to compartmentalize and study the game across different phases, and the subsequent sub-phases through the thirds. If you love analysis as much as we do, don’t forget to continue your journey in our Introduction to Football Analysis course, now available for $59.99.

See the entire course curriculum and jump around by visiting:

Introduction to Football Analysis – Online Course with Rhys Desmond

Thanks for reading and see you soon!

YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY…

Chaos vs. Control: A Collision of Principles

Some like to approach games in a disciplined structure, intentionally and meticulously dictating games to their own tempo. Others opt for a more emotionally-charged philosophy, reliant on the belief, energy and willpower of their trusted eleven on the field.

Game of Numbers #37 – Forge FC’s use of centre-backs in midfield like Manchester City

For the unfamiliar, Forge FC are the Manchester City of the Canadian Premier League. They play a possession-based 4-3-3, stacked with ball-savvy savants, and a culture that embodies winning. The Canadian Premier League’s been around since 2019 now. Forge have won the Playoffs in four of the five seasons, and lost the final in the…

Why centre-backs are becoming fullbacks: The tactical trend that defined 2023

It might be wrong to credit this tactical approach to Pep Guardiola. After all, the origin story to the ‘fullback’ is because the defender was fully back. However, in operating with a centre-back that steps up into midfield, Guardiola also created a construction within his team that regularly positioned centre-backs out wide. From then on,…

Comparing the Canadian Premier League’s next best centre-forwards

The best strikers in the modern era are able to combine a vast array of skillsets. We’ve seen this play out in the CPL this season, with those unable to fully combine all the necessary skillsets also failing to turn their talents into goals. Here is my analysis of four of the next best centre-forwards…

4 thoughts on “Breaking down the phases of the game”